Lionfish (Pterois volitans, Pterois miles), venomous fishes native to the Indo-Pacific and Red Sea, are the first invasive species of fish to establish themselves in the Western Atlantic (Schofield 2009).

Although they are quite beautiful, they are also skilled predators capable of eating any fish or invertebrate that will fit in their gaping mouths, and they have venomous spines that can cause serious injury to people.

The Invasion

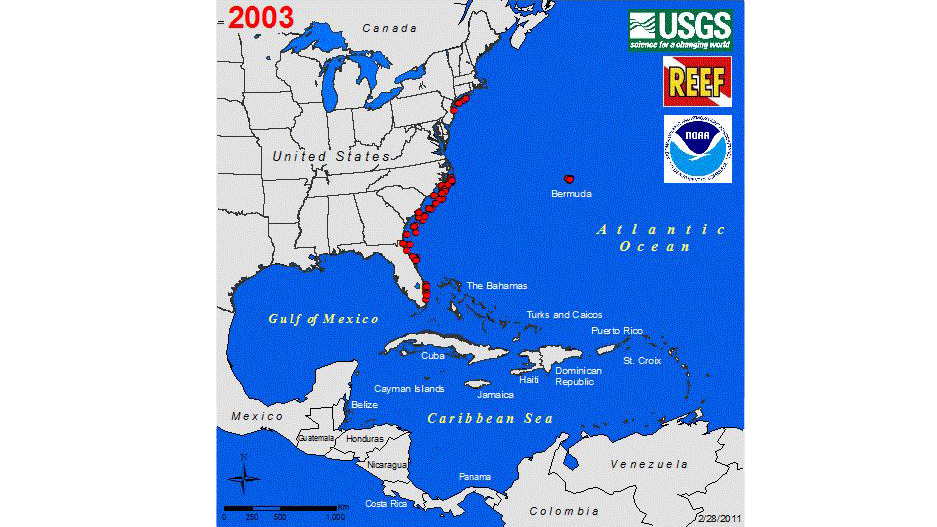

The first lionfish recorded in the Western Atlantic (east coast of the United States, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf) was a specimen captured near Dania, Florida in 1985. No other lionfish sightings were reported until 1992. The most likely source of these fish was the home aquarium trade.

At first, the spread of the lionfish population was rather gradual, but in 2000 the number of sightings began to increase exponentially. By 2009, lionfish were pretty well established along the Atlantic coast and throughout the Caribbean.

In 2010, sightings were also recorded in the northwestern Gulf, along the coasts of Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana. In July 2011, the first lionfish was observed in the sanctuary, at Stetson Bank.

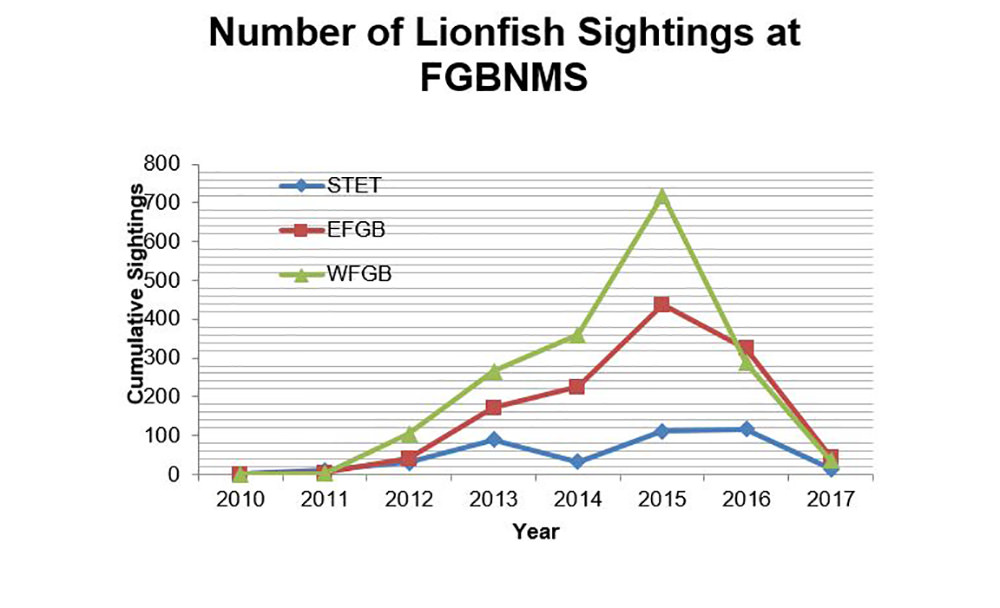

By the end of 2015, over 2,600 lionfish were observed within the sanctuary. About 1,500 of those were successfully removed and analyzed for important data.

| Year | Stetson Bank | East Flower Garden Bank | West Flower Garden Bank |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2011 | 11 | 4 | 2 |

| 2012 | 30 | 40 | 105 |

| 2013 | 89 | 172 | 265 |

| 2014 | 32 | 232 | 363 |

| 2015 | 112 | 437 | 720 |

| 2016 | 116 | 325 | 288 |

| 2017 | 14 | 44 | 35 |

| Lionfish Totals | 404 | 1247 | 1774 |

The Problems

Lionfish are indiscriminate eaters. If it fits in their mouths, they will eat it! This includes many smaller species of fish and invertebrates that are important herbivores, keeping algae in check on the reef. It also includes the young of commercially important fish species, such as snapper and grouper. Not only can this affect the ecological balance of the reef system, but it may also impact fisheries.

Lionfish have 18 venomous spines. Thirteen spines are found at the front of the dorsal fin, two at the front edge of each pelvic fin, and one at the front edge of the anal fin. An encounter with a lionfish can have painful consequences for people and potential predators.

Lionfish reproduce year round. Mature females (>1 year old) release 50,000 eggs every three days for the rest of their lives. Most reef fishes only spawn once a year, so lionfish may quickly outnumber native fish populations.

Lionfish have no natural predators in their invasive range. We're not entirely certain what eats lionfish in their native range, but it's most likely large predators like grouper, snapper, eels and sharks. We're hopeful that the same predator groups here will some day figure out that they can eat lionfish, but that won't happen quickly and it won't help in areas that have already been overfished.

Lionfish aren't recognized as predators. This is known as prey naivete and results in native fish and invertebrates not knowing to avoid lionfish to keep from being eaten.

The Response

Experts say it is unlikely that we will ever be able to completely eliminate lionfish from the Western Atlantic. So, the objective now is to minimize their impact on sanctuary resources. At this time, sanctuary policy is to remove any lionfish encountered. Research has shown that targeted removals in localized areas can be an effective control mechanism.

Most of the lionfish removed from the sanctuary are dissected and evaluated as part of ongoing research to learn more about invasive lionfish populations.

Permits for lionfish removals have been issued to a recreational dive charter that frequents the sanctuary to assist us in this effort. Permits are also issued for the annual, sanctuary-managed Lionfish Invitational, a derby-like event that allows recreational divers to assist in a mass removal and survey effort.

Without appropriate permits, sanctuary regulations only allow for removal of lionfish by traditional hook and line fishing methods.

What You Can Do

1. Make sure you aren't part of the problem. DO NOT release non-native species of any kind into your local ecosystem. Not all will survive, but those that do become established can wreak havoc. Lionfish are just one example.

2. Participate in removal events in places where they occur. Derbies are hosted at regular intervals in the Florida Keys and many other Caribbean locations. FGBNMS hosts more structured Lionfish Invitationals that also serve to collect important scientific information.

3. Spread the word!