Hard corals are the building blocks of coral reefs, and the mainstay of the coral cap at Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary. Soft corals are completely missing from this area of the sanctuary.

A Coral by Any Other Name

Hard corals are just one type of coral, but they are known by many common names that may be used interchangeably.

- stony corals

- reef-building corals

- hexacorals

- hermatypic (her'-mah-tip-ik) corals

- scleractinian (sklayr-ak-tin'-ee-an) corals

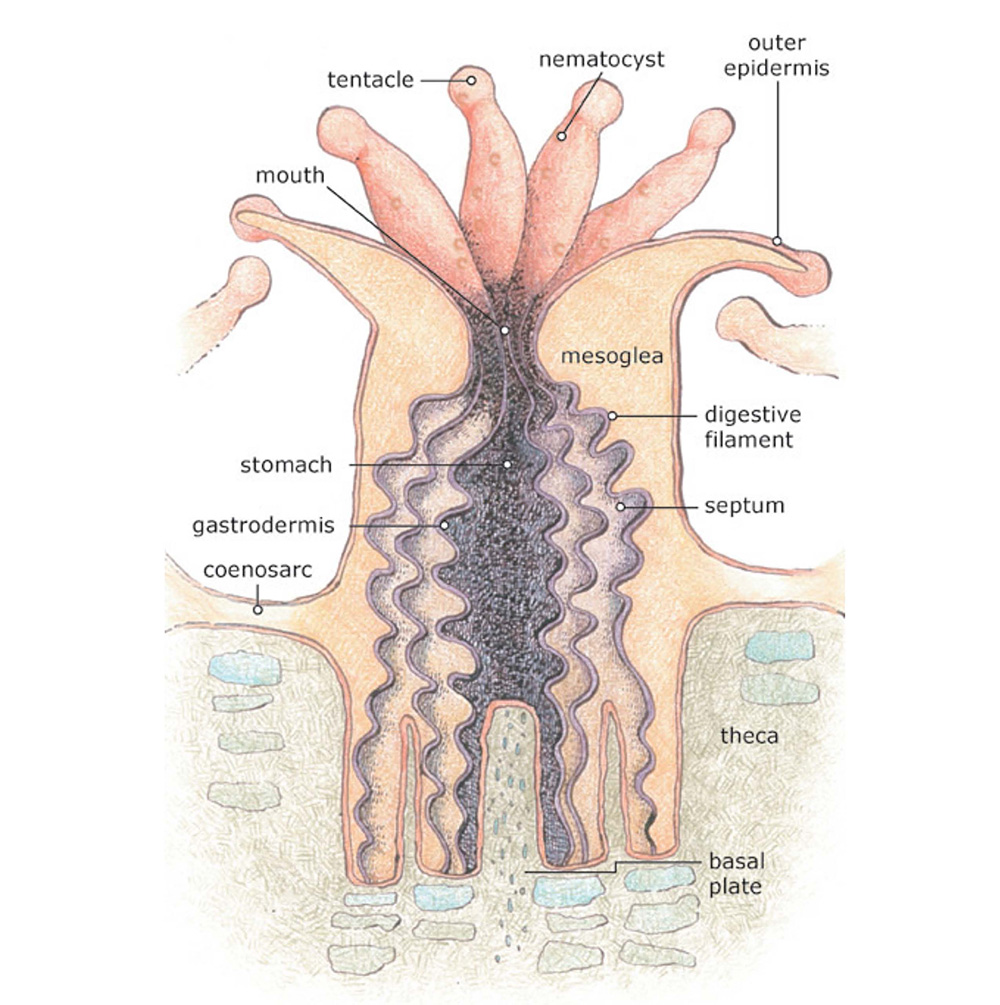

Coral Polyps

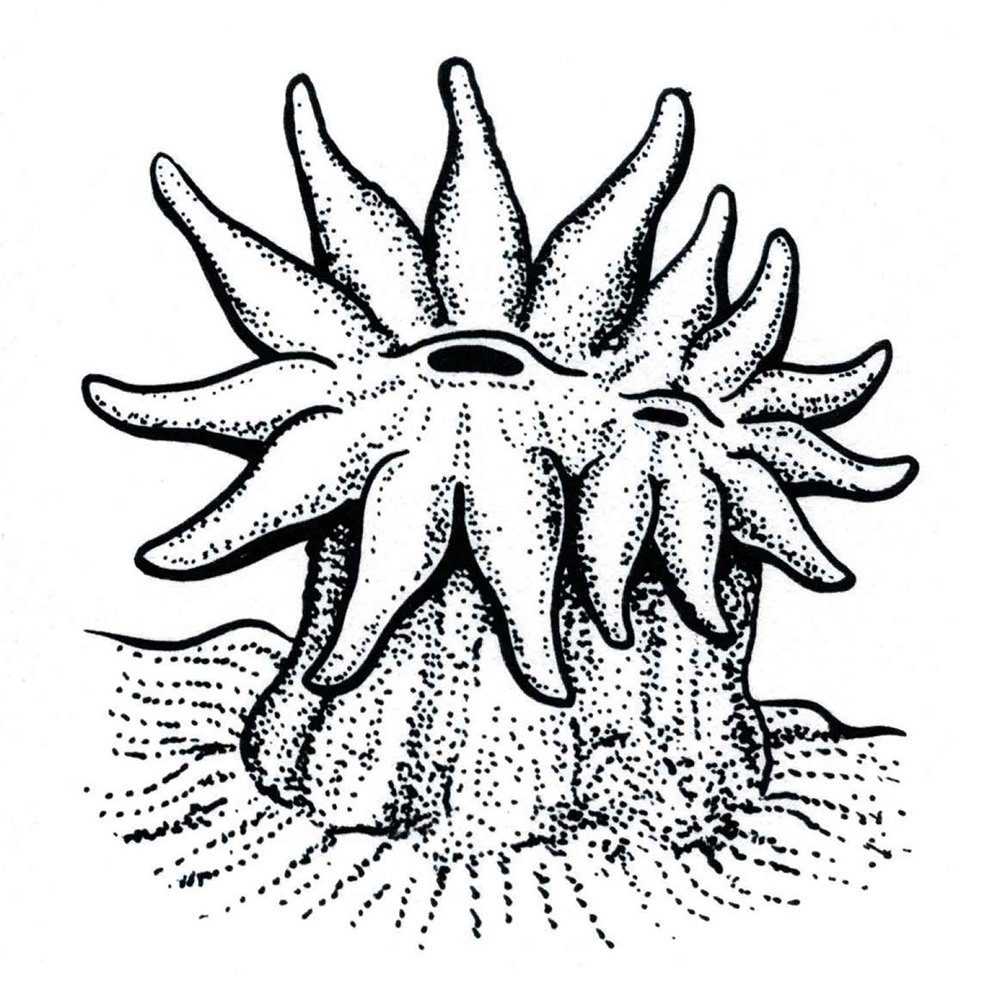

The coral animal is made of many polyps that look like miniature sea anemones. Each polyp generally ranges in size from one (1) to ten (10) millimeters across, although the polyps of some species may be larger.

Like an anemone, a coral polyp has a soft, tubular body topped by a ring of tentacles. In reef-building corals, the tentacles and several other body parts occur in multiples of six (6), which is why they are sometimes referred to as hexacorals.

The mouth, its only opening, is located in the center of the tentacles.

Coral Skeletons

Unlike an anemone, a reef-building coral polyp builds a hard (stony) external skeleton that forms a protective cup (calyx or calice) around its base. This skeleton is made of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) in a form known as aragonite.

Over time, the polyp continues to lay down additional layers of skeleton (basal plates) beneath itself. You can see an animated image of How Stony Corals Grow on the NOS website.

These layers form annual growth patterns, much like tree rings.

Hundreds to thousands of coral polyps together make up a reef-building coral colony. Each polyp is connected to the next by a thin layer of tissue (coenosarc), creating a living mat over a shared skeleton.

Polyp Partners

Most people think of corals as being very colorful, but reef-building coral polyps are actually transparent. The color we see comes from symbiotic algae, known as zooxanthellae (zo-o-zan-thel'-ee), that live within the tissues of the polyps.

Through the process of photosynthesis, the algae use sunlight and carbon dioxide to create food and oxygen. This food provides up to 70% of the necessary nutrients for reef-building corals to survive.

Reef-building corals get the remainder of their nutrients by capturing small plankton with their stinging tentacles (raptorial feeding) or through direct absorption of minerals from the surrounding seawater.

Asexual Reproduction

Reef-building corals reproduce both sexually and asexually.

Asexual reproduction takes place in the form of budding or splitting polyps. This is how a colony grows.

In splitting, the original polyp divides (splits) in two, then each of those polyps repeats the process, and so on for the rest of their lives. Each new polyp is an identical genetic reproduction of the first, so all of the polyps in a colony are genetically the same.

In budding, a new polyp grows out of the side of an existing polyp, much like the bud on a plant. Despite the slight difference in method, the result is the same--a genetically identical polyp.

Sexual Reproduction

Sexual reproduction is a chance for mixing of genetic material and the creation of completely new colonies. About 75% of reef-building corals are broadcast spawners, while the rest are brooders.

In broadcast coral spawning, colonies release gametes (eggs/sperm) into the water in large quantities. The gametes float to the surface where egg and sperm join to form free-floating planula larvae.

The planulae travel with the currents for up to two weeks before settling to the bottom as polyps. Once firmly attached to a hard surface, the polyps will then begin the process of asexual reproduction to create colonies.

Coral spawning at Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary takes place 7-10 days after the full moon in August each year. It is one of the most spectacular coral spawning events in the world due to the large concentration of mass spawning corals on our reefs.

In brooding, only male gametes (sperm) are released into the water. These float along on the currents until they are captured by female polyps with eggs. Fertilization takes place inside the females and results in planula larvae.

These larvae are later released and settle to the bottom soon after. However, they don't tend to settle as far from the parent colonies as the larvae from broadcast spawners, perhaps because of the shorter settlement period.