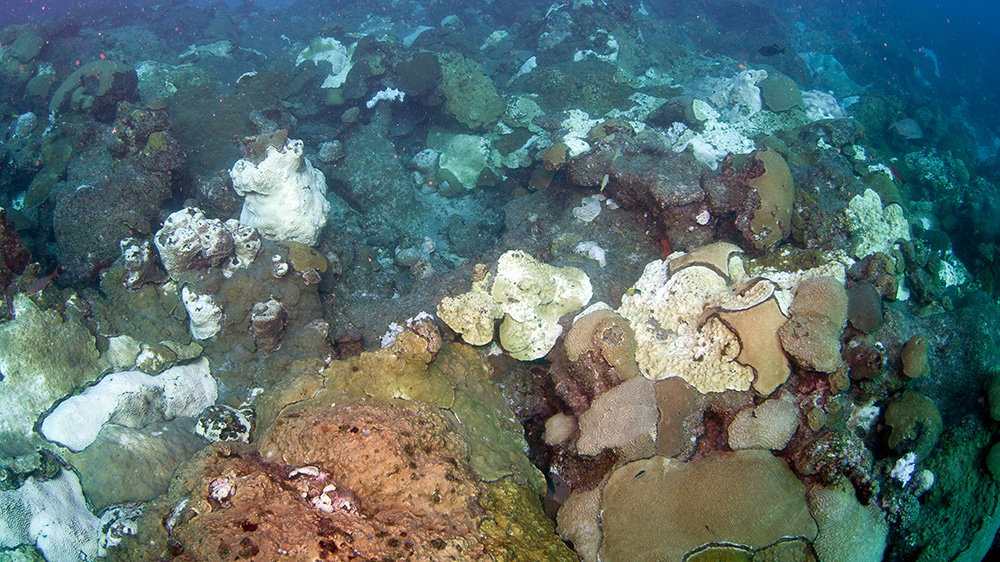

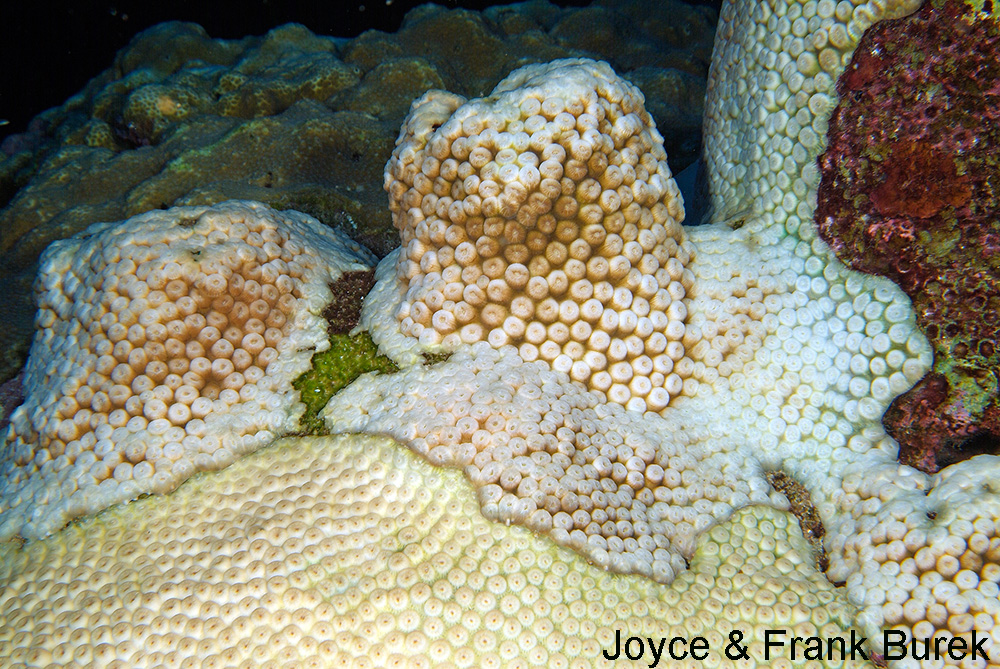

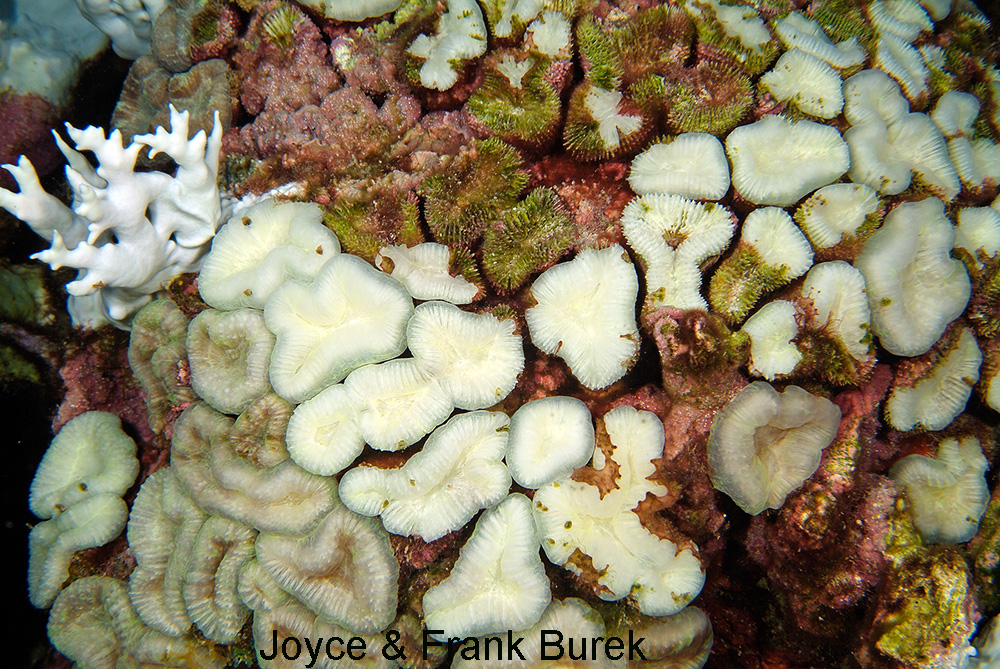

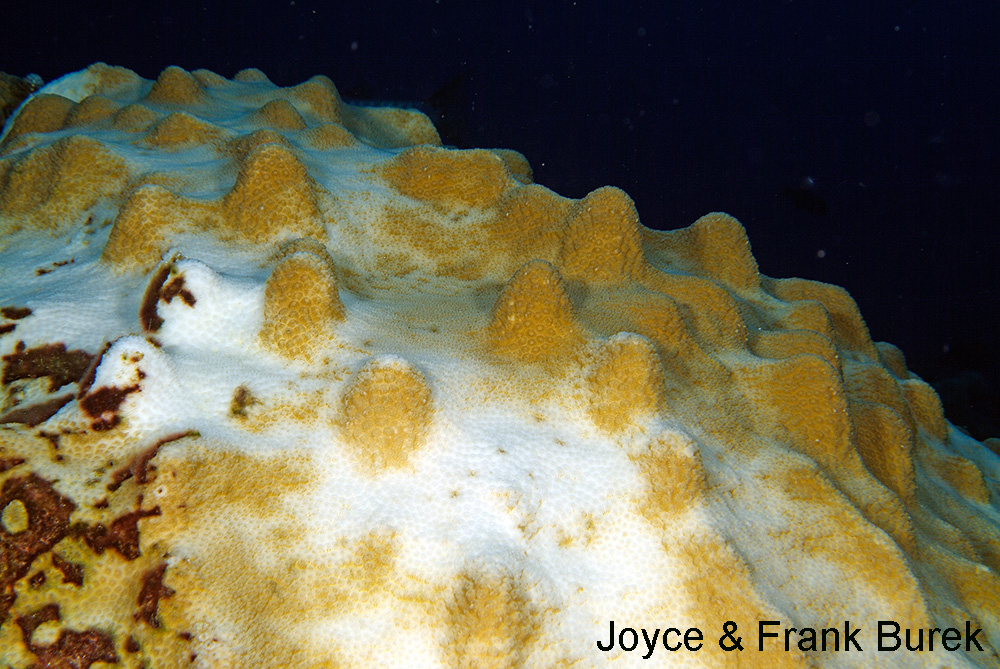

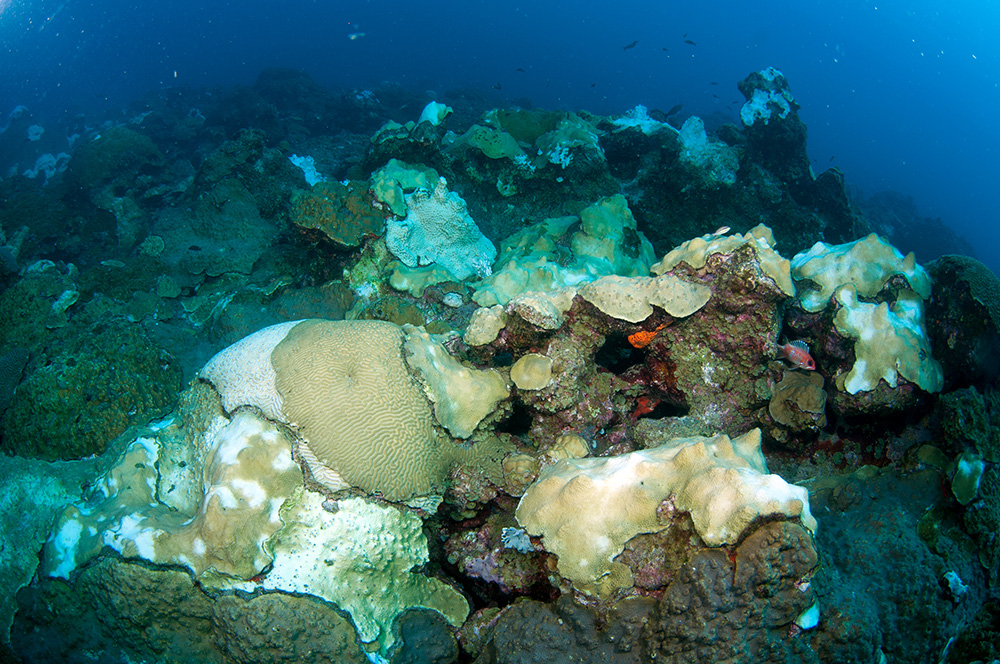

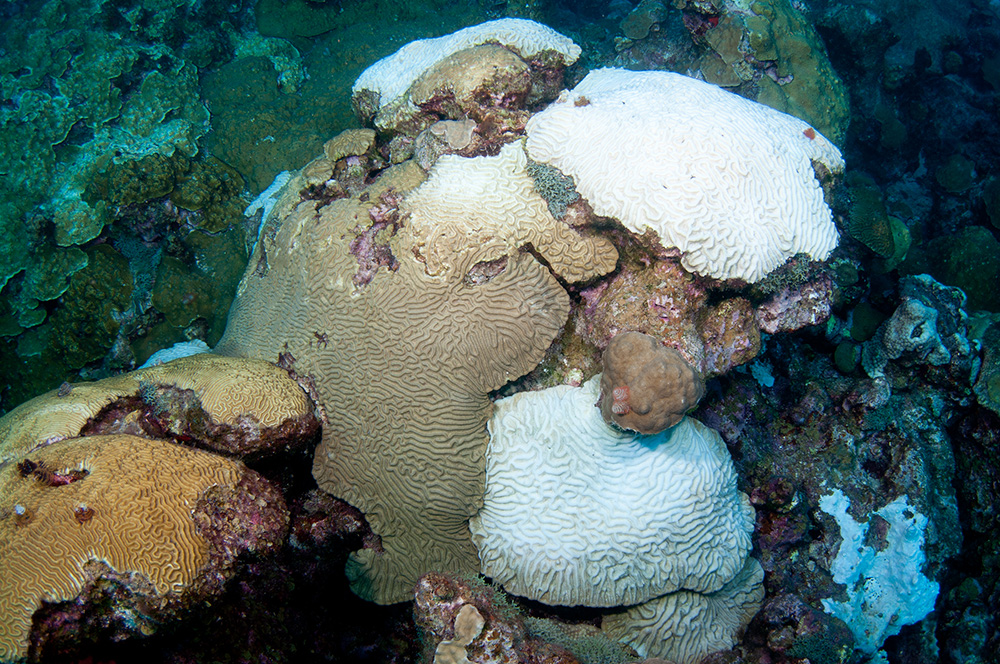

Coral bleaching describes a situation in which corals appear to turn white.

This happens when coral polyps expel their symbiotic algae (zooxanthellae) as the result of some kind of stress event. Without the algae, the coral polyps are mostly clear, allowing you to see through to their white skeletons beneath. This results in a bleached appearance.

The good news is that coral bleaching is not necessarily a death sentence. If stress conditions are alleviated in time, the corals may take on new algae and return to a healthy state. Even so, recovery may take weeks to months and recently stressed corals may be more susceptible to coral diseases.

The bad news is that by the time we can see bleaching, the process has already been taking place for some time. In addition, without the algae present to provide a majority of their food, the corals are beginning to starve.

If the stress event continues for too long, the corals will eventually die, leaving just their skeletons behind.

For a better understanding of how corals and zooxanthellae interact, please visit our Coral Basics page.

Environmental Stresses

Stresses that may lead to bleaching include extremes in salinity, pollution, sedimentation and temperature. The key word here is "extreme." Any of these factors may fluctuate on a given day, but when the changes are severe or last for too long, bleaching may occur.

Most coral bleaching is the result of water temperatures that go beyond the corals' level of tolerance for too long. This usually means temperatures that are too high, but can also mean temperatures that are too low.

Reef-building corals survive within specific temperature ranges that vary slightly by region. At the Flower Garden Banks, their preferred temperature range is about 68-86F (20-30C).

The longer elevated temperatures continue, the more zooxanthellae leave and the paler the coral color becomes. When enough zooxanthellae leave, the coral looks bleached.

Bleaching generally starts later at the Flower Garden Banks than at other reefs in the Caribbean because warm temperatures typically persist late into fall in this region. We may not see evidence of bleaching until September or October, while other Gulf and Caribbean reefs may see evidence as early as July.

Bleaching may affect an entire colony or only part of it. It may affect only some species and not others. In fact, it may even affect only certain colonies of a particular species while leaving other colonies of the same species untouched.

Sea surface temperatures were consistently high in the Gulf during the summers of 2005, 2010, and 2016, causing major bleaching events in the sanctuary. Similar problems were seen on coral reefs around the world those same years.

So far, we haven't seen any bleaching in the sanctuary as a result of cold water temperatures. However, in February and March of 2010 water temperatures fell below 60F (16C) for several days in Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary and caused quite a bit of coral bleaching and death in shallow reefs there.

Measuring Temperature

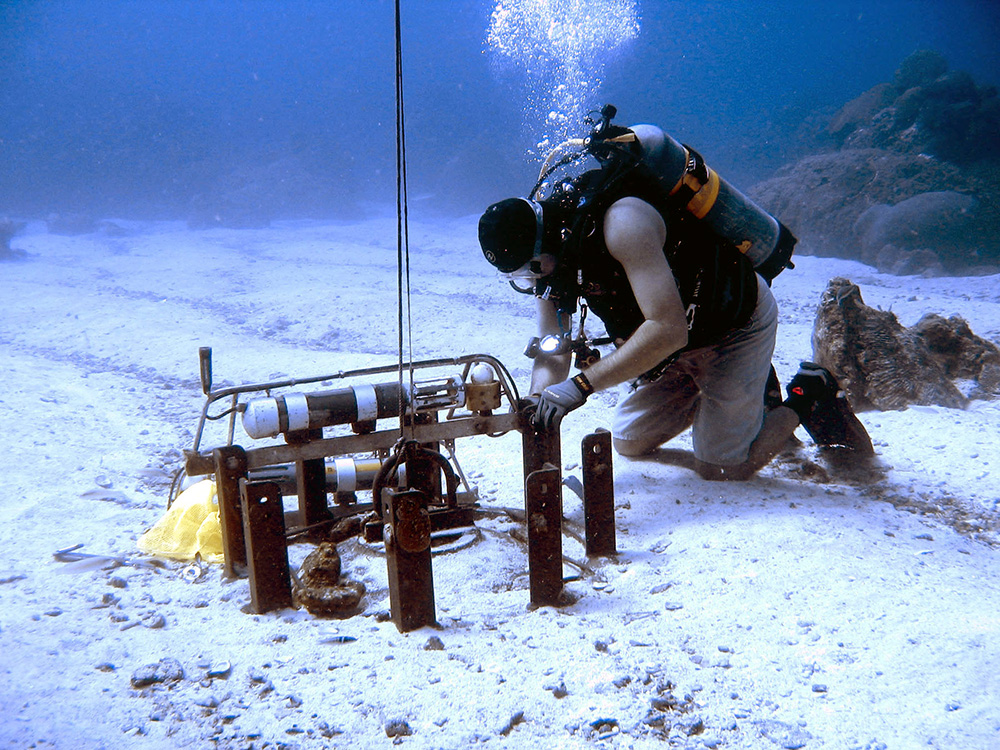

How do we know what water temperatures are on the reef when we're in our offices in Galveston?

We have water quality instruments on the sea floor at East and West Flower Garden and Stetson Banks throughout the year. These sensors continuously record data that we can download to a computer each time the sensors are retrieved and maintained. This happens at least every 3 months, under normal circumstances.

In between data downloads, we can track daily temperatures in the sanctuary using satellite measurements of sea surface temperature (SST). While this doesn't tell us the temperature down on the reef, it does give us an estimate.

Remote Sensing System

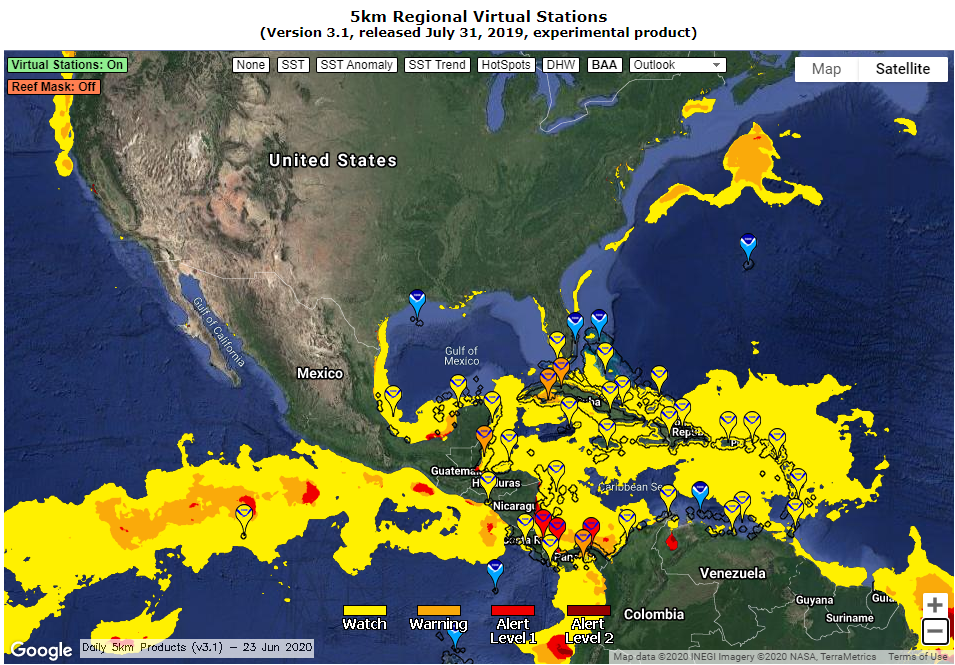

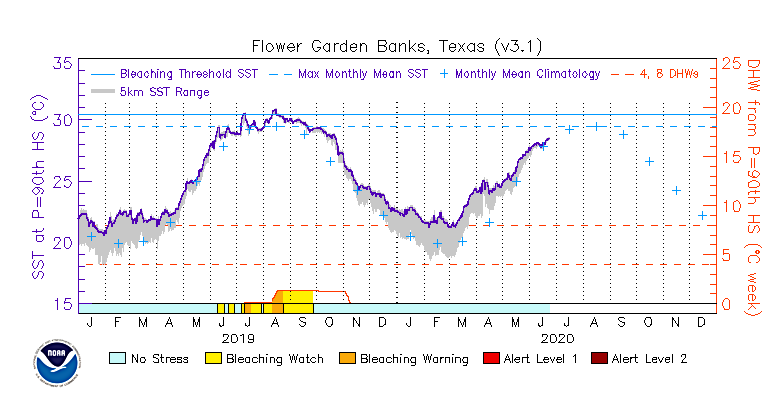

Satellite data on Sea Surface Temperature (SST) is the basis of a Remote Sensing System coordinated by NOAA Coral Reef Watch across the globe.

Through this system, scientists monitor SST at over 30 sites in the Caribbean and Gulf, including Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary. They then compare that data to historic temperature averages to determine the likelihood of coral bleaching at each location.

Data graphs on that web site give a first-hand look at how close temperatures are to the bleaching thresholds and average monthly temperatures. You can also sign up for bleaching alert emails to receive notifications of any change in status at the sanctuary or one of the other sites.

For more information on how this system works and what the temperature graphs show, please visit the Satellites & Bleaching Tutorial on the Coral Reef Watch web site.