The Flower Garden Banks were first discovered by snapper and grouper fishermen in the early 1900s. They named the banks after the sponges, plants, and other marine life they could see on the colorful reefs below their boats.

Discovery and Exploration

Although fishermen had been visiting the Flower Garden Banks for a while, the first scientific study of the area didn't take place until 1936, when the banks were included in a hydrographic survey of the Gulf conducted by the U.S. Coast & Geodetic Survey (now the National Ocean Service, which includes the Office of National Marine Sanctuaries). The survey provided valuable information about the geology and topography of the banks.

Using the data from the 1936 survey and other surveys conducted in the 1950s, researchers determined that the banks were actually underwater formations created by salt domes, plugs of salt pushing the overlying sediments upward.

In 1953, Henry Stetson, a geological oceanographer with Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (WHOI) was the first to identify the existence of corals on the Flower Garden Banks.

In 1960, a group of eager divers led by Dr. Thomas Pulley, Director of the Houston Museum of Natural Science, made the first underwater exploration of the Flower Garden Banks to determine the truth behind fishermen's stories of coral reefs in the northern Gulf.

Some scientists thought the area would be too cold, or too turbid, to support any extensive coral reef development. However, these scuba diving explorations revealed that the Flower Garden Banks supported healthy, pristine coral reef systems.

In Need of Protection

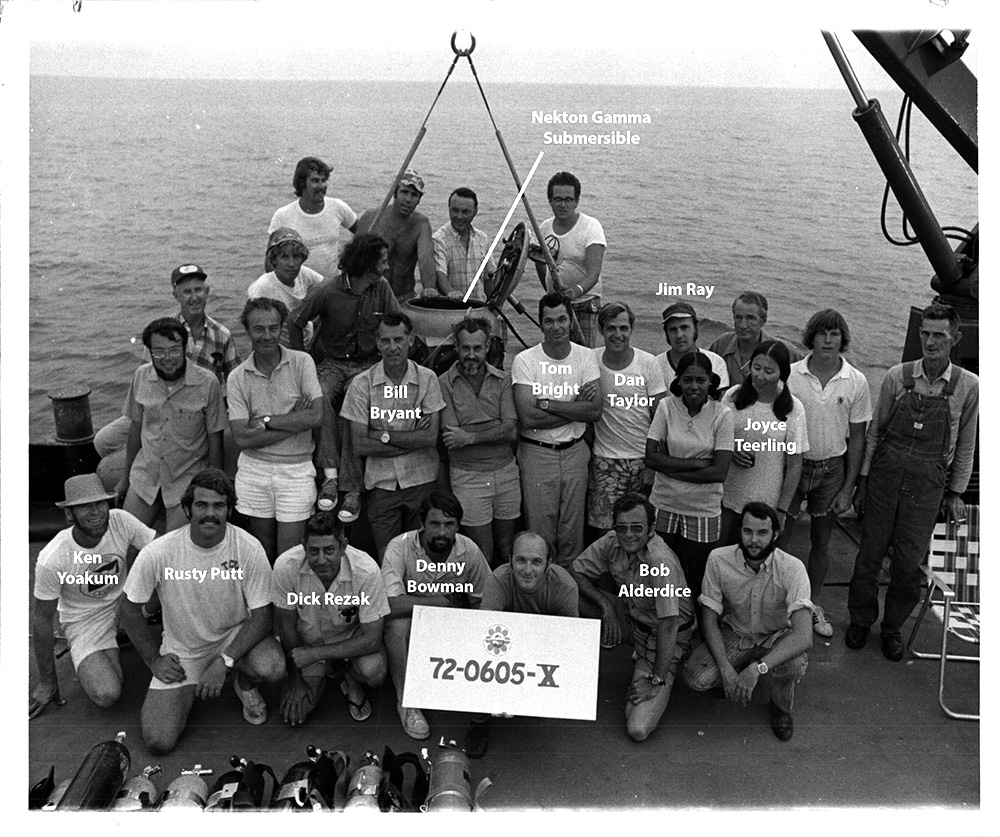

In the late 1960s, Robert Alderdice and James Covington established the Flower Gardens Ocean Research Center (FGORC), heralding a period of intense multi-agency, interdisciplinary research, which continues to this day. Results of this research prompted government agencies to begin discussing the need to protect the banks from increasing human activities, including oil and gas extraction, anchoring and the harvesting of fish, corals and other invertebrates.

With passage of the National Marine Sanctuaries Act (NMSA) in 1972, researchers began discussing the Flower Garden Banks as a candidate for designation as a National Marine Sanctuary. By then, recreational divers were also excited about the Flower Garden Banks. Houston Underwater Club led the charge and submitted a formal letter of nomination in 1979.

Due to a number of issues, it was 13 years before President George H. Bush ultimately signed the document designating the Flower Garden Banks as our 10th National Marine Sanctuary on January 17, 1992. Stetson Bank was added to the sanctuary in 1996.

Sanctuary Beginnings

During the 20 years leading up to designation, Dr. Tom Bright and his graduate students at Texas A&M University worked steadily to explore the banks and conduct research that would ultimately form much of the knowledge base for managing the resources. Not content to merely collect data, Dr. Bright took an active role in seeking protected status for the Flower Garden Banks. When researchers captured an anchoring incident on video, he made certain the video became a catalyst in the designation process.

Considered by many to be the ‘father’ of the sanctuary, Dr. Bright was not about to allow initial funding issues impede its success. As Director of Texas Sea Grant, he established a partnership with the fledgling sanctuary. Part of Sea Grant’s contribution to the partnership included free office space in its College Station facility during the sanctuary’s first year. Although this location was a considerable distance from the coast, it actually helped solidify the sanctuary’s close ties with the research community.

First Years

Dr. Steve Gittings was selected as the first manager (and sole employee!) of the sanctuary. He brought several years of Flower Garden Banks research to the new position. Under his leadership, sanctuary programs flourished.

Working partnerships with the Minerals Management Service (now known as BOEM and BSEE) continued to enhance historic protective measures of the banks related to oil and gas industry activities. Research partnerships were expanded to include additional universities and government agencies. Education and outreach efforts were initiated. Volunteers were recruited. Education and research coordinators were brought on board.

Support from the recreational dive community, oil and gas industry, government and private sectors grew steadily during the sanctuary’s first ten years. These partnerships were responsible for the addition of Stetson Bank to the sanctuary in 1996.

Continued Planning

In 1999, transfer of leadership to Mr. George “G.P.” Schmahl heralded a subtle shift in management focus for the sanctuary. Drawing upon his extensive management and research experience with Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, G.P. continued to build on the strong foundation previously established. As the sanctuary continued to mature, program efforts transitioned from straight exploration focused research and public awareness, toward more issue-based research and outreach.

During his tenure, many projects focused on the connectivity between sanctuary banks and other reefs and banks along the outer continental shelf. He also guided the sanctuary through development of its first Condition Report in 2008, and an updated sanctuary Management Plan, which was released in 2012. This plan recommended sanctuary expansion, a process which took another nine years to complete. Under G.P.'s guidance, sanctuary expansion finally became a reality in 2021.

International Recognition

On October 27, 2012 Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary was formally listed under the Special Protected Areas and Wildlife (SPAW) Protocol of the Cartagena Convention. Eligible sites for listing under the SPAW Protocol are those coastal and marine areas that are ecologically important to the Wider Caribbean region.

In signing the SPAW Protocol, the U.S. committed to take the necessary measures to protect, preserve and sustainably manage areas that require conservation to safeguard their special value, and threatened or endangered species of flora and fauna. Such areas include representative habitats, critical habitats, economically and/or socially valuable areas, and areas of special significance.

Sanctuary Expansion

On January 19, 2021, after approximately 14 years of scientific analysis, consultation, and public input, the sanctuary was expanded to include portions of 14 additional reefs and banks across the northwestern Gulf. This increased the sanctuary size from 56 to 160 square miles.

Next Steps

In November 2023, Dr. Michelle Johnston took the reins of the recently expanded sanctuary. Since 2010, Michelle has served in a variety of science roles within the National Marine Sanctuary System, first at headquarters and later with Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary (FGBNMS). She also served as acting deputy superintendent at National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa and acting superintendent at FGBNMS after G.P.'s retirement.

While serving as the sanctuary's research coordinator, Michelle led staff through the development of its first Climate Vulnerability Assessment and an updated Condition Report, both set for release in 2024. Collaborating with staff and other Gulf reef researchers, she also worked to determine science needs for the sanctuary moving forward. Under her guidance, the sanctuary is now ready to develop its next Management Plan.