LIONFISH RESEARCH

The sanctuary research team works closely with other government and non-government agencies across the Gulf and Caribbean to better understand the invasive lionfish problem and work toward solutions.

Lionfish dissections give us data that is helpful in understanding the lionfish problem. Photo: FGBNMS/Drinnen

As part of this effort, a certain amount of data collection is conducted with each specimen removed from the sanctuary. Initially, all of the following data was collected from each specimen, but as the volume of specimens increases, only a certain percentage receive the full work-up.

Once captured, lionfish are placed in labeled bags noting when and where each specimen was collected. The specimens are then frozen until ready for processing.

317 lionfish were thawed in tubs and coolers for processing in September 2015 following the first Lionfish Invitational. Photo: FGBNMS/Drinnen

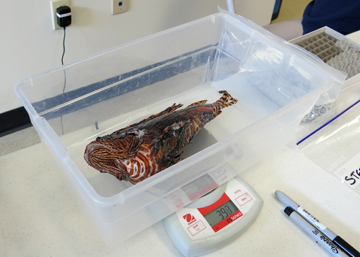

Once thawed, weight and length data is collected on every lionfish removed from the sanctuary. This includes two measurements--total length and standard length (from the nose to the point where the tail attaches to the body).

A lionfish being weighed on an electronic scale (weight in grams). Photo: FGBNMS/Drinnen

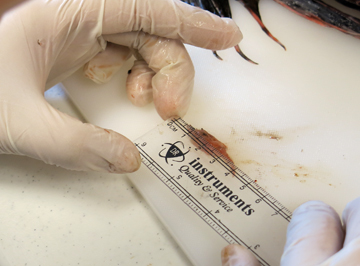

A lionfish being measured, in centimeters.

Photo: FGBNMS/Drinnen

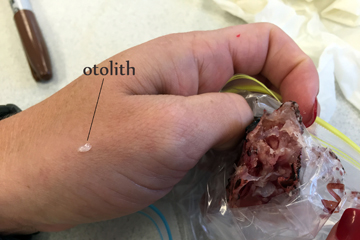

The lionfish's head is removed and sent off to a researcher who is sampling the otoliths (ear bones) of lionfish to determine their ages. Since otoliths are very small (about .5 cm), it is easier and less time-consuming to send the whole head.

A researcher displays an otolith on her hand after extracting it from the lionfish head on the right. Photo: FGBNMS/Drinnen

By examining the growth rings in the ototliths, researchers can tell how old a fish is. When coupled with the weight and length data, this helps us understand how quickly lionfish are growing in their invasive range.

A 2021 publication based on this research shows that the oldest lionfish recorded in the northwestern Gulf was found at West Flower Garden Bank in 2018. Interestingly, his age of 10 years places him in the area before the first lionfish were observed in the sanctuary (2011).

Close up view of an otolith on the researcher's hand. It measures about .5 cm. Photo: FGBNMS/Drinnen

top of page

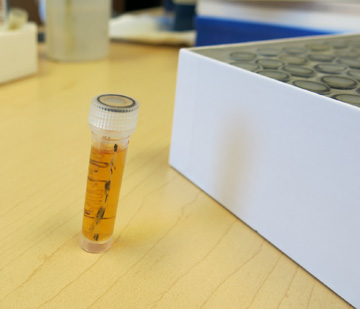

Fin clips are taken from either the dorsal and/or anal fins to be sent off for research on lionfish genetics.

A researcher clips a small section from the soft part of the dorsal fin. Photo: FGBNMS/Drinnen

Genetic data tells us how lionfish are related throughout the invasive range. So far, scientists can trace all of the lionfish from the Western Atlantic/Caribbean/Gulf back to 10 original females!

Researcher Michelle Johnston places fin clips in small vials with liquid preservative. Photo: FGBNMS/Drinnen

Each fin clip is preserved in ethanol in a small, labeled vial. (Image: FGBNMS/Drinnen)

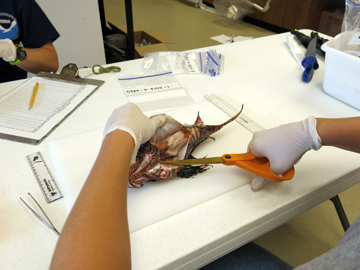

The abdomen is cut open to reveal the sex of the fish and allow us to examine the gut contents.

Researcher Marissa Nuttall cuts open the belly of a lionfish. Photo: FGBNMS/Drinnen

Most lionfish that we examine have globs of fat in their guts, an indication that these fish are overeating and becoming obese.

Off-white clumps of fat are often found surrounding the organs of a lionfish. Photo: FGBNMS/Drinnen

The stomach is cut open to see what the lionfish has been eating.

Extracting a small fish from the stomach of a lionfish.

Photo: FGBNMS/Drinnen

A blenny extracted from the lionfish stomach pictured above. Photo: FGBNMS/Drinnen

Some of the gut contents are fairly recent additions and relatively easy to identify. Those that are not are sent off for genetic analysis.

Three partially digested cardinalfish taken from a lionfish stomach. Photo: FGBNMS/Drinnen

So far, the most fish we have found in a single stomach is 15--11 damselfish and 4 blennies! The level of digestion indicated that they were all eaten at about the same time.

15 fish were taken out of the stomach of a lionfish about 9 inches long. Photo: FGBNMS/Drinnen

Each animal extracted from the lionfish stomach is recorded along with its size.

Michelle Johnston measures a relatively large damselfish (about 5.5 cm) found in the stomach of a lionfish. Photo: FGBNMS/Drinnen

Fish and invertebrates that cannot be identified are preserved in ethanol and sent off for DNA identification.

(Image: FGBNMS/Drinnen)

All of this data on the the lionfish prey allows us to determine what life stages of which species are being affected by the invasion.

Measuring a small fish removed from a lionfish stomach. Photo: FGBNMS/Drinnen

A partially digested Red Night Shrimp, the creature most commonly eaten by lionfish in the sanctuary. Photo: FGBNMS/Drinnen

Lionfish Stomach Contents

| Common Name |

Family/Class |

Percent Composition |

| Red Night Shrimp |

Rhynchocinetidae |

31.12 |

| Other Shrimp Species |

Penaeoidae |

17.63 |

| Wrasse |

Labridae |

8.47 |

| Blenny |

Blenniidae |

3.58 |

| Damselfish |

Pomacentridae |

3.27 |

| Cardinalfish |

Apogonidae |

1.70 |

| Parrotfish |

Scaridae |

1.44 |

| Goby |

Gobiidae |

.65 |

| Crab |

Crustacea |

.39 |

| Surgeonfish |

Acanthuridae |

.35 |

| Basslet |

Grammatidae |

.31 |

| Snapper |

Lutjanidae |

.26 |

| Grouper |

Serranidae |

.22 |

| Jack |

Carangidae |

.17 |

| Drum |

Sciaenidae |

.13 |

| Unidentifiable Fish |

|

16.02 |

| Empty Stomach |

|

8.08 |

| Chyme (digested mush) |

|

6.20 |

A listing of the most common fish and invertebrates found in lionfish gut contents.

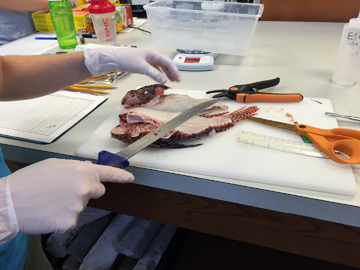

When a specimen is large enough, we filet the fish to get at least 100 grams worth of meat to send off for ciguatera testing. Since the sanctuary is a hotspot for ciguatera, we want to make sure lionfish aren't dangerous to eat.

Michelle Johnston filets a larger lionfish specimen so that meat samples can be sent for ciguatera testing.

Photo: FGBNMS/Drinnen

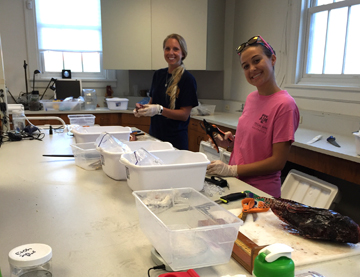

Each time we process lionfish, local Sea Aggies are invited to participate. This helps us with the large amount of data processing and provides valuable hands-on experience for marine biology students.

Sea Aggies helping with lionfish dissections in October 2014. Photo: FGBNMS/Drinnen

Sea Aggies helping with lionfish dissections in September 2015. Photo: FGBNMS/Drinnen

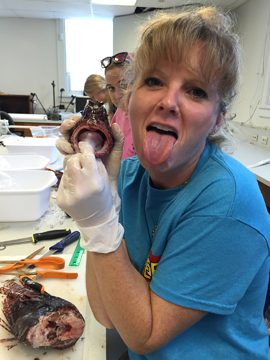

Processing hundreds of lionfish is hard work, but it is also rewarding knowing that we are contributing to a bank of knowledge that may some day help us overcome this invasion.

Science is fun! Photo: FGBNMS/Drinnen

For more information on the lionfish problem, please visit our Invasive Lionfish page.